Emanations of the Cross Throughout History

The wailing and gnashing of teeth over Pete Hegseth’s Jerusalem Cross tattoo showed massive historical ignorance of the Cross and its many forms over mankind’s history. Let’s rectify that.

Money, war, religion, markets, geopolitics, social dynamics, the human condition, and societal implications. As everyone with a platform spends their time hyperfocused on single issues that draw you in, this is my attempt to step back to show the larger picture (and potential implications or concerns).

The ever-changing media cycle seems built to give us the attention spans of fruit flies - but there are issues that we should take the time to focus on and understand.

These are those issues.

Topics covered in this post

Introduction: Ignorance, rewriting, obfuscation, and destruction of history, both religious and secular

Neolithic to Pre-Christian: Crosses Across Ancient History (10,000 BC - 3,000 BC)

Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Sumerian Cultures (3,000 BC - 1,000 BC)

Indus Valley, Bronze Age Europe, and Early Asian Traditions (c. 2,500 BC – 1,500 BC)

Pre-Christian Mediterranean (circa 1000 BC–1st Century AD)

Christianity (1st Century AD onward)

Fin

Introduction: Ignorance, obfuscating, rewriting, and destruction of history, both religious and secular

"Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards."

-Søren Kierkegaard

It is both interesting and telling to see how a person reacts when they come across something that they don’t recognize or understand. Anger, fear (which are often highly correlated), confusion, flippancy, or, for some of us - a deep desire to learn or understand that which we don’t already know.

When the thing not recognized is either a cryptic symbol or what appears (to the person in question) to be an altered version of a religious or Faith-based symbol that they do know or recognize, many will be quick to anger and name-calling without even a moment of due diligence or question asking.

We all know the cautionary tales of mobs with pitchforks and torches or the Salem witch trials, and yet they happen pretty routinely in our modern day, albeit in a lesser form and on social media rather than in the physical town square.

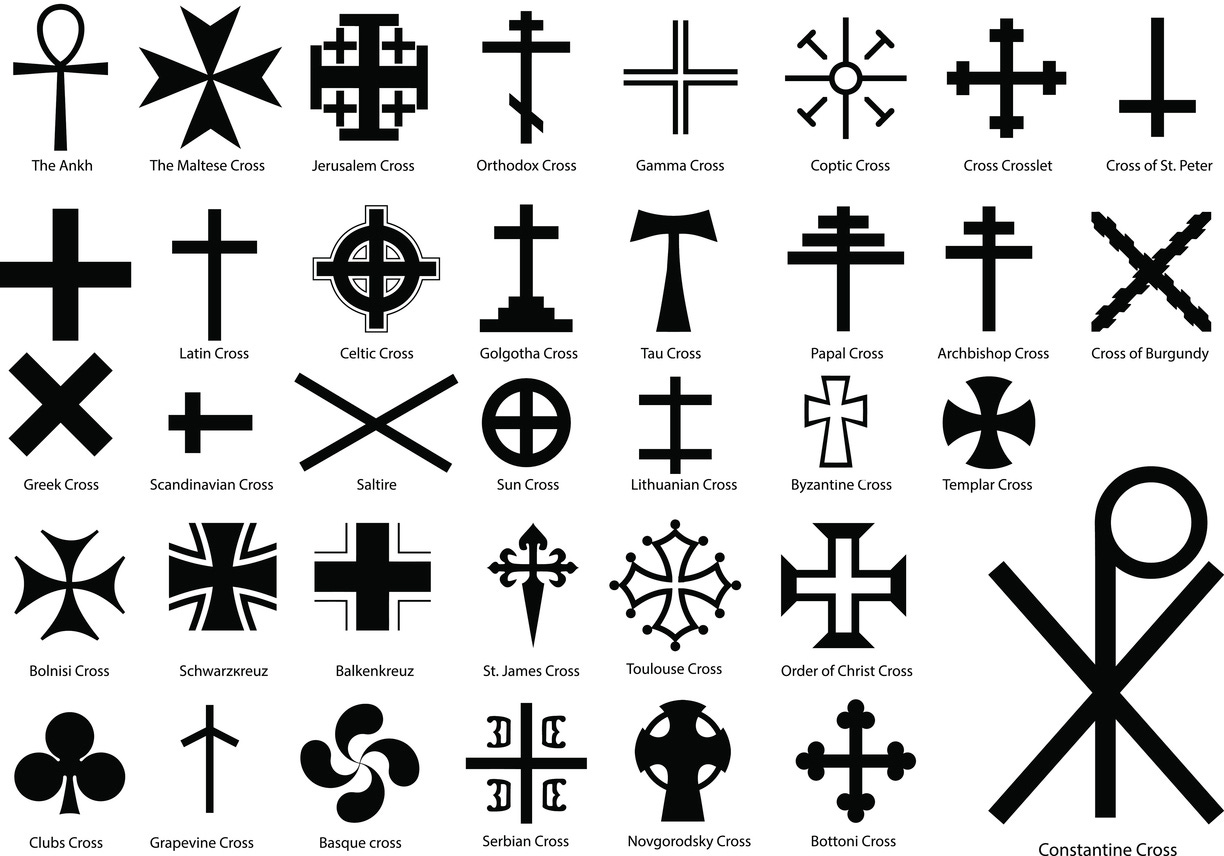

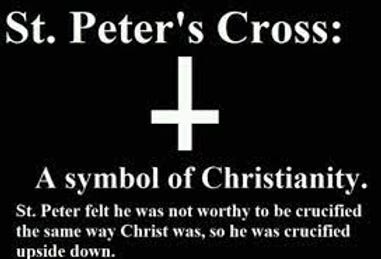

For instance, take the Cross of St. Peter in the graphic that is used as the hero image for this post.

Notice anything peculiar about it?

Does it rile something strange inside of you when you see it?

While many modern Christians are only familiar with the Latin Cross (shorter horizontal bar than the center post), it is far from the only version of the Cross that is and has been used in Christianity.

Like Pete Hegseth’s Jerusalem Cross tattoo, which so many in the media, secular, and historically illiterate Christian communities made an enormous hubbub over, each version of the Cross used within the Christian Faith has a specific meaning to its usage.

Good Christians who read their Bible but allow themselves to be quick to anger may know the Scripture quite well, but the long history of groups who have desecrated the meaning of an upside down cross will short-circuit their brains to cause anger and/or fear rather than understanding its (pretty obvious) meaning.

St. Peter was crucified upside down, at his own request; when the verdict came down for him to be crucified, he stated that he was not deserving of a death that would make him seem like Christ Jesus of Nazareth, so they honored his request in a pretty despicable way.

As such, the original meaning of the St. Peter’s Cross was to signify that occurrence.

The Pope is a descendant of St. Peter (metaphysically), so it may be worn by him in that symbolic nature.

Internet forums are quick to tell you that wearing it means the Pope is satanic - but that goes against the very Biblical teaching of who St. Peter was, how he was crucified, and what it actually means.

Within the Christian Faith, there have been many different versions of the Cross used over time since Christ was crucified, and the first few centuries of Christian symbols did not even consist of Crosses.

Earliest members of the Faith were horrified that a symbol of Christ’s execution would be used as that of redemption - and the Cross wasn’t generally used for the Faith until Constantine converted and made the Latin Cross the widely-recognized symbol of Christianity (313 AD).

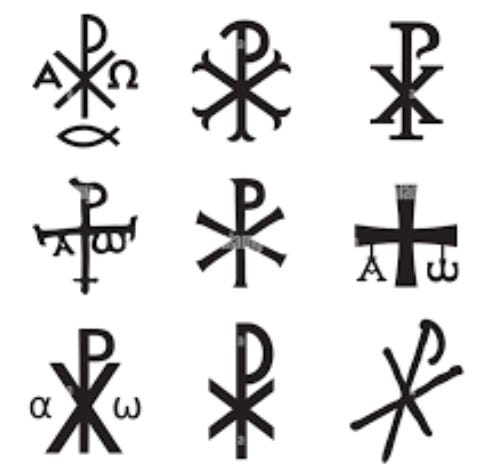

Even Constantine’s vision of a Cross in the sky before the Battle of Milvian Bridge was not a Cross in the way that most Christians or secular people would recognize today. Known as the Chi-Rho Cross, it was one of the symbols used by the earliest Christians combining the first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek:

We’ve previously discussed in the On Statecraft and Religion series how the ichthus (the “Jesus fish”) was used by some of the earliest Christian, and two members unknown to each other drawing one half of it in the sand was one of the earliest versions of “pass and signs” tradecraft used to identify themselves to each other.

But here’s something that, although accurate history, may make some people upset: the Cross was used as a symbol, for both secular and Faith traditions, long before Christ Jesus of Nazareth walked the earth.

In the tradition of using this platform to educate and inform people about as much deep history as I can, we will use this post to help people understand the Cross and the many versions (that we know of) in which it has been used throughout mankind’s history and pre-history.

Each was symbolic for its own reason, but in my opinion the symbolic nature took on a far deeper and more significant nature in the time since it became synonymous with Christianity.

Without further ado, let’s begin walking down a path that has been with mankind as far back as anyone can trace.

Neolithic to Pre-Christian: Crosses Across Ancient History (10,000 BC - 300 AD)

Prehistoric and Neolithic Crosses (10,000 BC to 3,000 BC)

While it is impossible for us to say that we “know” when the first version of a cross began to be used in a symbolic form or exactly what it was used to represent, there are some pretty darned good educated guesses that can be made based on where they have been found, the context in which they seem to have been used, and the dating methods to give a fair estimate as to the age of things.

Students and professional investigators of deep ancient history are often astounded at the level of understanding that the ancients had for the world around them, and in many instances for the celestial movements of our solar system.

This keen understanding was represented in different parts of the world through different stories used to teach, name seasons, stars, constellations, and symbols of the zodiac, but the same archetypal symbols show up around the world in ancient cultures who were trying to understand and teach other about the world around them (and the unseen world that many of them held reverence for in different ways).

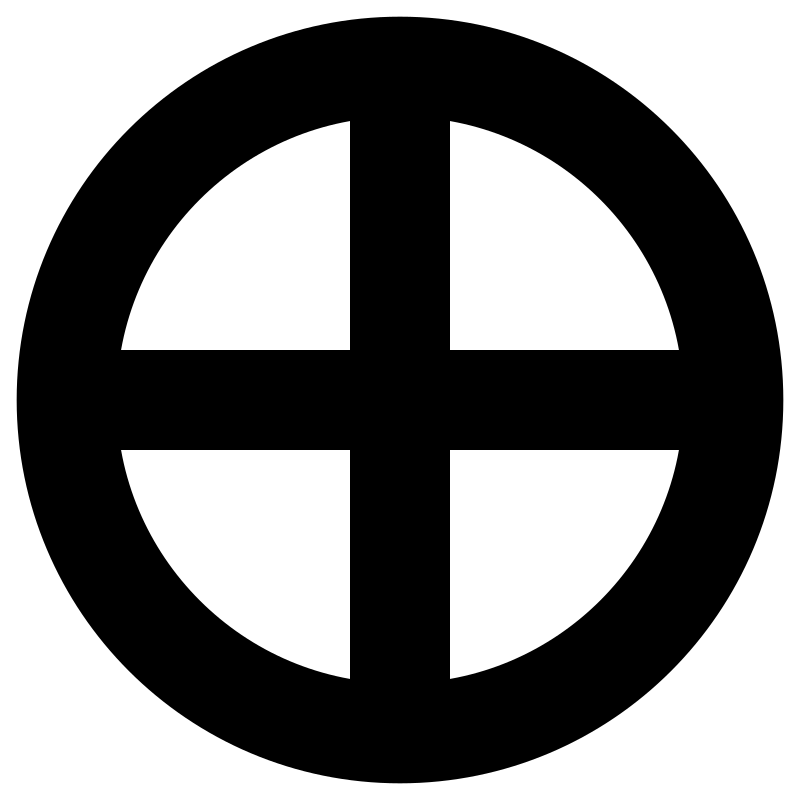

The “solar cross” or “sun wheel” (pictured above) is one of those ancient archetypes that is seen in many places, and has also picked up different changes, meanings, and accouterments across the millennia.

In its representations in prehistoric cave art (like that found in Lascaux, France), it is often believed to have been used for directional markers or solar symbols. Moving into the Neolithic Era, it is believed to have been used to represent the sun, the four cardinal directions, and/or the four seasons of the year.

Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Sumerian Cultures (3,000 BC - 1,000 BC)

In ancient Mesopotamia, the cross appeared in cuneiform scripts and art, sometimes linked to deities or celestial bodies. For instance, a cross with arms of equal length (like the Greek Cross) was associated with the sun god Shamash.

The Sumerian and Akkadian civilizations used cross-like symbols in cuneiform script and religious iconography.

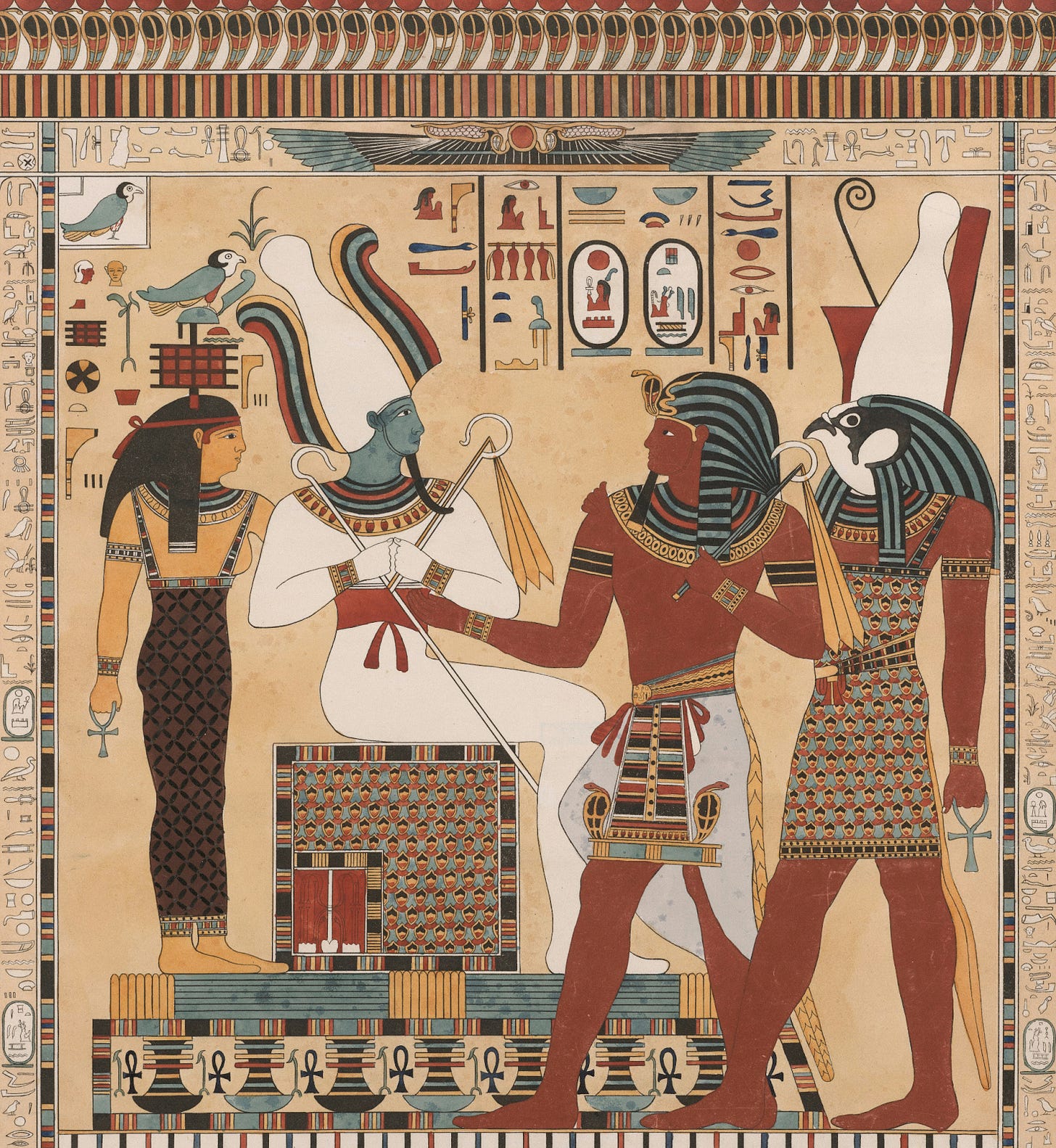

It was in Egypt, however, that we began to see the cross be used heavily to denote different things.

A lesser known and early version of a cross used by the Egyptians was the Tau cross, which looks like an uppercase T in our modern context.

It was used to symbolize things in later cultures that we know from preserved writings (St. Francis of Assisi used a Tau Cross), but in the Egyptian and early Mediterranean cultures it is thought to have represented the god Tammuz.

The ankh is more often associated with Egyptian symbols. It is sometimes called the "cross of life," and some translations of the word say it simply means “cross with a carrying handle.”

This looped cross symbolized life, immortality, and divine power, and it was frequently depicted in the hands of gods and pharaohs. While not a simple cross, it shows how the shape was adapted into a culturally specific emblem.

Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash

Indus Valley, Bronze Age Europe, Nordics, Celtics, and Early Asian Traditions (c. 2,500 BC – 500 BC)

Crosses began to pop up more in very different ways across all of Eurasia within this 1,500-year period.

In the Indus Valley (modern day India and Pakistan) we began to see one of history’s most nefarious uses of a cross symbol - but it was only made nefarious by a later implementation that bore no resemblance (and many would say categorically opposite usage) of the original.

This was the “hooked cross” in its original form, symbolizing good fortune and the sun’s motion. It has been seen on seals, pottery, shrines, temples, and many other places from Scandinavia to Asia.

An early version of a cross with four arms bent at right angles, clockwise or counterclockwise, it was only over a millennium later to be repurposed for its nefarious form that is more recognizable to Westerners - the swastika.

The Celtic cross motifs began to emerge between 2,500 BC and 500 BC, and it has been found in Bronze Age artifacts across Europe.

This may very well be the latest version of the cross as a symbol before the time of Christ that seems recognizable to most today. But again, it began to emerge several thousand years before Christ Jesus of Nazareth walked the earth.

The Celtic cross, often featuring a ring around the intersection, symbolized the sun and cosmic unity in early Druidic traditions. While the Druids are often talked about, most of their “mysteries” and learnings were strictly prohibited to be written down in any form, and were only communicated through oral traditions.

As such, most of our understandings of the symbolism and rituals are guesswork, or what has been hobbled together from outside observations of their practices at the time.

Scandinavian and Germanic tribes used Tau crosses (T-shaped crosses), possibly linked to Thor’s hammer or protective symbols. We mentioned previously that St. Francis of Assisi used the Tau Cross, so it’s a mystery if this Tau Cross on Tory Island (Ireland) that has been dated to the 7th century is of Christian, Nordic, Germanic, or Celtic origin - nobody seems to know.

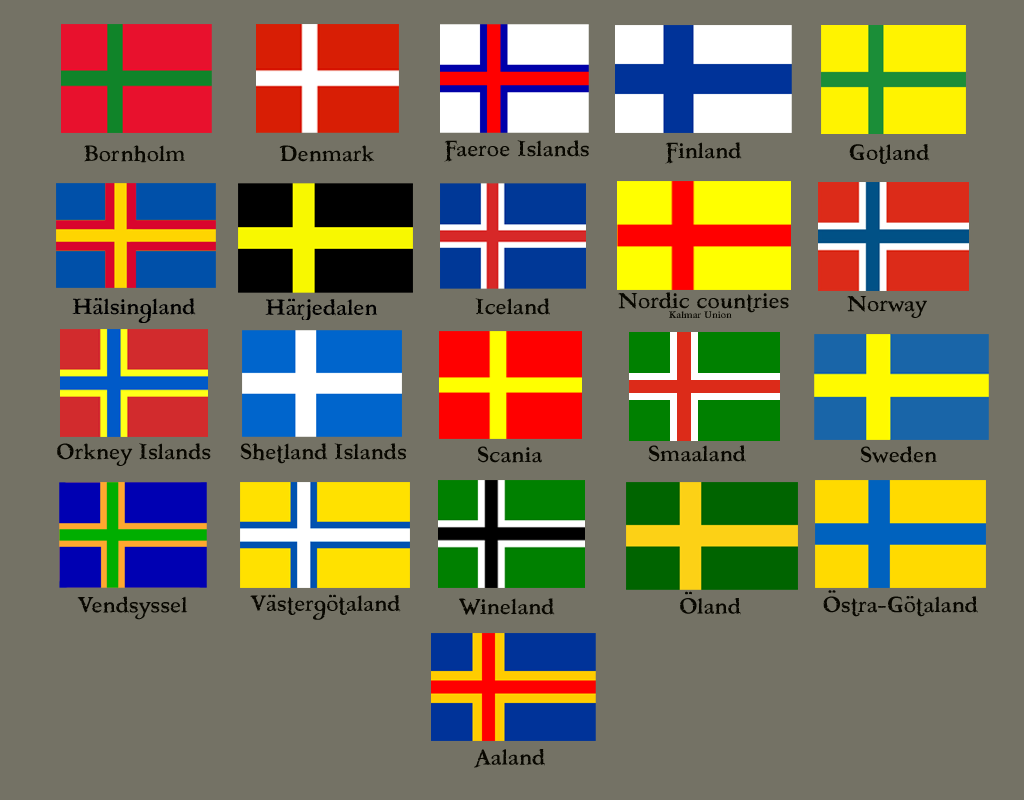

If you’ve ever looked at Nordic flags before, you may have noticed something similar across them all - the Nordic cross:

A version of the cross even began to show up in China around 2,000 BC. The Shizi (cross shape) appears in oracle bone script and early cosmology, tied to balance and the universe’s structure.

Pre-Christian Mediterranean (circa 1000 BC–1st Century AD)

The Tau cross continued its archetypal journey across mankind and emerged in various cultures during the Greco-Roman period. The Romans and Greeks both used various cross-like symbols in military standards (still in use by the USMIL today), architecture, and religious artifacts.

Crucifixion was a Roman method of execution, and the cross became associated with suffering before its later religious transformation. While crucifixion is largely thought of as a Roman invention, they were far from the first to use it - but, in true Roman form, they certainly perfected its brutality and efficiency.

In ancient Greece, the Tau cross was linked to the god Attis and rituals of renewal.

The Crux Ansata (the ankh or “cross with a handle”) also influenced Greco-Roman iconography, blending into mystical traditions like those of the Gnostics. Students of ancient history know that most of the scholars who worked at the Library of Alexandria were Greeks and Jews, and from their writings, the commerce of the time, and Alexander the Great’s conquests, Egyptian culture, art, and lore spread into many other places.

In the Levant, the Tau cross appeared in Hebrew traditions as the "Tav," the final letter of the alphabet, sometimes interpreted as a sign of finality or one of Divine protection (e.g., Ezekiel 9:4 in the Hebrew Bible).

If you’re not up on your Book of Ezekiel, here’s a reminder:

"Yahwe said to him, 'Go through the midst of the city, through the midst of Jerusalem, and set a mark upon the foreheads of the men that sigh and that cry for all the abominations that be done in the midst thereof.”

In this verse, God instructs a man to mark the foreheads of men who are lamenting the wickedness in Jerusalem. The mark is an act of mercy, as God will not destroy his Faithful worshippers. Some believe that “mark” was one of the Tau cross, based on its symbolic meaning (Divine protection) and the meaning of this verse.

Christianity (1st Century AD onward)

It’s important that we note a couple of things here before we move forward:

The cross was used as an archetypal symbol for as far back as can be traced before the crucifixion of Christ Jesus of Nazareth upon the Cross. While the earliest Christians did not associate the Cross (as we know it) or Crucifix as a symbol of Christianity, that changed with Constantine’s conversion.

While the Romans are most associated with crucifixion due to their doing it to Christ Jesus of Nazareth, they did not begin the practice of crucifixion, nor did they invent the practice of crucifixion being done upon a cross. They did, however, make it more brutally efficient.

Before the Romans practiced crucifixion, its use can be recorded as far back as the Assyrians and Babylonians (9th century BC and earlier), Persians (6th century BC), and Greeks (5th-4th century BC).

The practice was abolished by Constantine in 337 AD due to its association with Christianity.

Now that we have that ugly part of the historical use of the cross and crucifixion out of the way, let’s dive into how that event shaped a changing world and what the Cross represents to the Faithful now.

As discussed above, the earliest symbolic representations of Christianity were not a Cross or Crucifix as we know it, but other versions like the Chi-Rho Cross (the Greek letters chi and rho set over one another) or the ichthus (fish).

Another less known early version was the Staurogram (⳨), a monogram combining the Greek letters tau (Τ) and rho (Ρ), resembling a crucified figure. The ICXC NIKA Cross is also found in Byzantine Christian art, sometimes called the “Jesus Christ Conqueror’s Cross.”

There have been many representations (emanations) of the Cross since it became used as the symbol for the Christian Faith, and they each - like Pete Hegseth’s Jerusalem Cross - have a specific meaning and symbolism that many, even among the Christian Faithful, do not know or understand.

Let’s go through as many as we can now. I will include pictures and the symbolic purpose for as many as I can.

The Latin Cross

Put forward by Constantine after his conversion, this is now largely seen as the most recognizable Christian cross, symbolizing Christ Jesus' crucifixion. It is used to symbolize:

The crucifixion of Jesus, and the atonement of sins. It's also known as the crucifix or Crux immissa.

Selflessness: The cross symbolizes Christ's selflessness and devotion to humanity

Atone for sins: The cross symbolizes Jesus' sacrifice and atonement for the sins of the world

Victory over sin: The cross symbolizes the significance of Jesus' death as a victory over sin

The Greek Cross

A symmetrical cross used in Eastern Christianity and Byzantine art. Unlike its Latin counterpart, it was not meant to symbolize the cross Jesus died on, but the church itself - spreading the gospel to the North, South, East, and West, as well as the four platonic elements.

This version of the cross was also used by Pythagoras of Samos pre-Christ as a symbol to represent geometry (equal length arms) and the four elements (earth, air, wind, and fire).

The Greek Orthodox Cross

The Cross most commonly associated with the Greek Orthodox Church has a long bottom stem and shorter length head and arm stems. The defining features of this form are the tips of the stems, which have rounded protrusions in each of the 3 outward directions (symbolising The Trinity).

The meaning of this cross is based on the crucifix of the sacrifice. In this sense it is more like the Latin Cross than the Greek Cross, but the rounded "protrusions" signify a projection of God's grace (similar to the meaning inherent in the Maltese Cross).

The shape of this Cross is also represented in the floorplan of most Greek Orthodox Churches.

The Tau Cross

Used by St. Francis of Assisi and the Franciscan Order. In his usage of the Tau Cross, it is representative of a journey never completed this side of Heaven.

In the Franciscan Order, it is also used to symbolize:

Conversion: A turning away from sin and toward God

Penance: A reminder to turn away from sin and toward God

Service: A call to serve the least, such as the leper and the outcast

God's love and healing: A reminder of the goodness and love of God

Peacemaking: A challenge to live as peacemakers and to promote the healing of all creation

St. Francis’ use of this Cross is quite in-line with his frequent use of saying, “Let us begin again,” indicating that, like one of the most basic precepts of the Christian Faith, “death is not the end.”

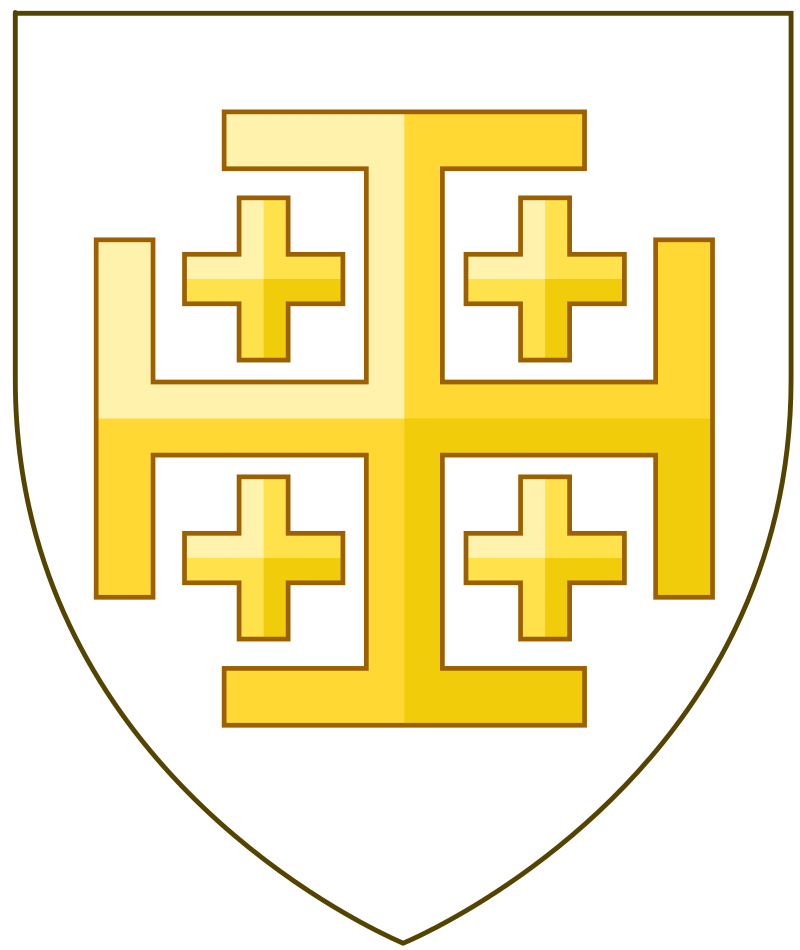

The Jerusalem Cross (Pete Hegseth’s Tattoo)

Today, the Jerusalem Cross is still the main insignia of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem - the Latin Catholic diocese for the Holy Land - the Custody of the Holy Land run by the Franciscan Order, and the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem.

A large cross surrounded by four smaller crosses, some say it represents Christ and the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). Similarly, another symbolic meaning is that it represents Christ’s command to spread the Gospel around the world.

Another interpretation is that the 5 elements of the Jerusalem Cross represent Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross through His 5 wounds.

https://www.ncregister.com/news/jerusalem-cross-what-is-it-history-and-meaning

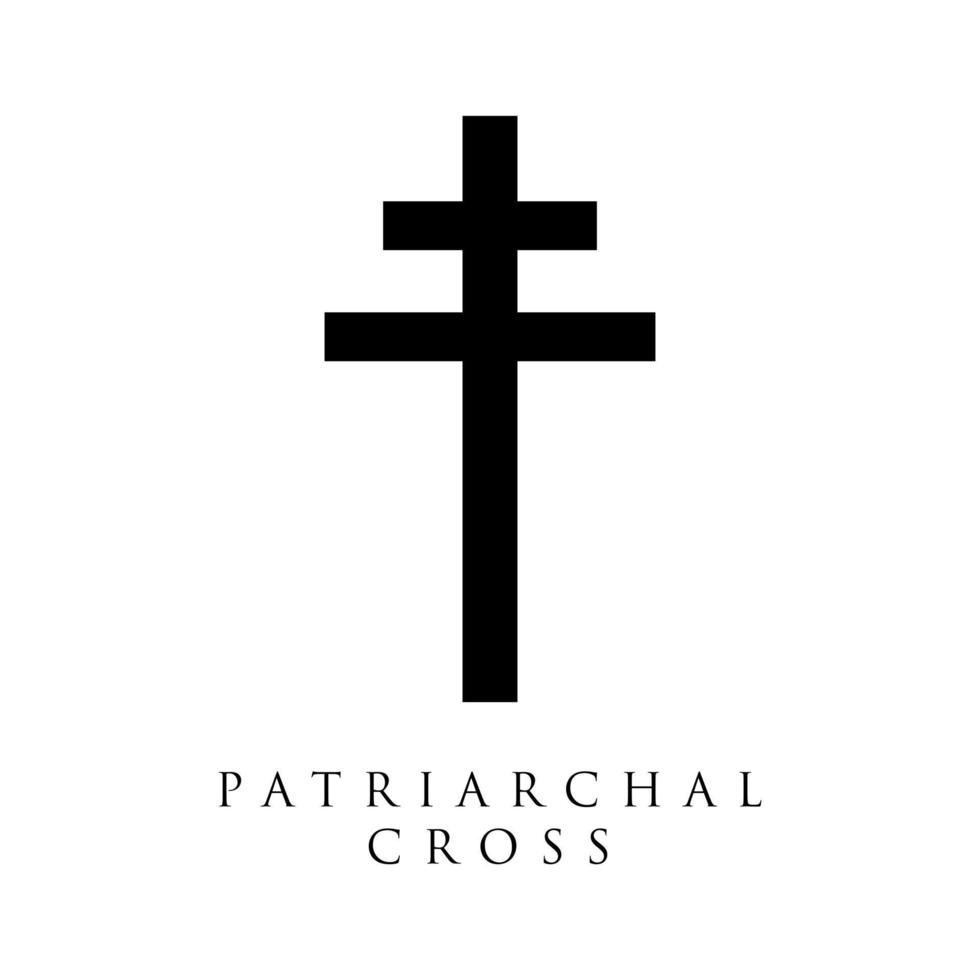

The Patriarchal Cross

A cross with two horizontal bars, often linked to bishops and the Eastern Orthodox Church. While often confused with the Cross of Lorraine, this is different in stylization.

The Patriarchal Cross also has different opinions on its symbolism. The first is that in its beginning uses during the Byzantine era, the first horizontal line represented the secular power, and the second the ecclesiastical power of the Byzantine emperors.

Another interpretation is that the first horizontal line represents the death, and the second line the resurrection of Christ Jesus.

The Papal Cross

A Cross with three horizontal bars, this symbolizes the 3 realms of the Pope’s influence: the Church, the earth, and Heaven.

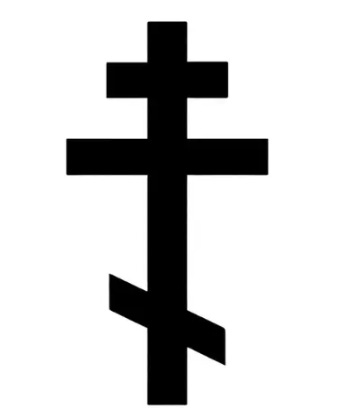

The Russian Orthodox Cross

Features a short top bar (titulus), middle bar (arms), and slanted bottom bar (footrest). This symbolic use of the Cross represents the crucifixion of Christ in a different form than the Catholic usage of the Crucifix.

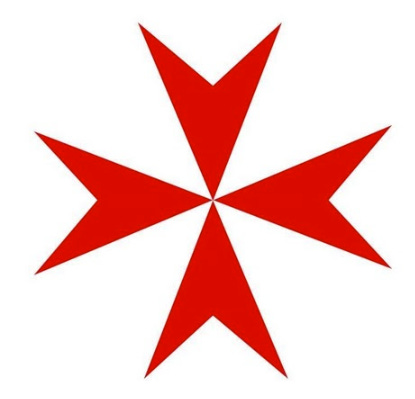

The Crux Patté / Maltese Cross

An eight-pointed cross used by the Knights Hospitaller. The term "Maltese Cross" has been used to describe a great number of shapes—sometimes correctly, sometimes not. Essentially it's a Greek Cross whose central touch-point is narrower than the arms are towards their full extension.

The design etymology of the cross comes from earlier heraldic crosses of equal arm length, which in turn were derived from the Greek Cross in both form and meaning. The key difference being a more centralized point of origin, leading to a more stylized presentation.

The word "Pattée" actually means "footed" (as in; the arms splay out towards the ends as an animal's foot might do). "Maltese" of course refers to the island of Malta, but the form's use by people all over the world diminishes any real geographic association.

The "Maltese" cross has been used all over the world. It's been on both sides of some wars at the same time. It's the base shape of the US Naval Cross, The Victoria Cross, and the Iron Cross—all awards given by opposing sides in WWII. It has been used by hundreds of municipalities from Moscow to Spain in their heralds due to its history as a popular medieval symbol.

One bit of commonality is an association with courage. Simply looking at it might tell you why: It looks strong. Its splayed-out form depicts both protection from harm and a projection of strength.

*the above description of the Maltese Cross was taken from https://athenagaia.com/pages/cross-forms-shapes-styles-history

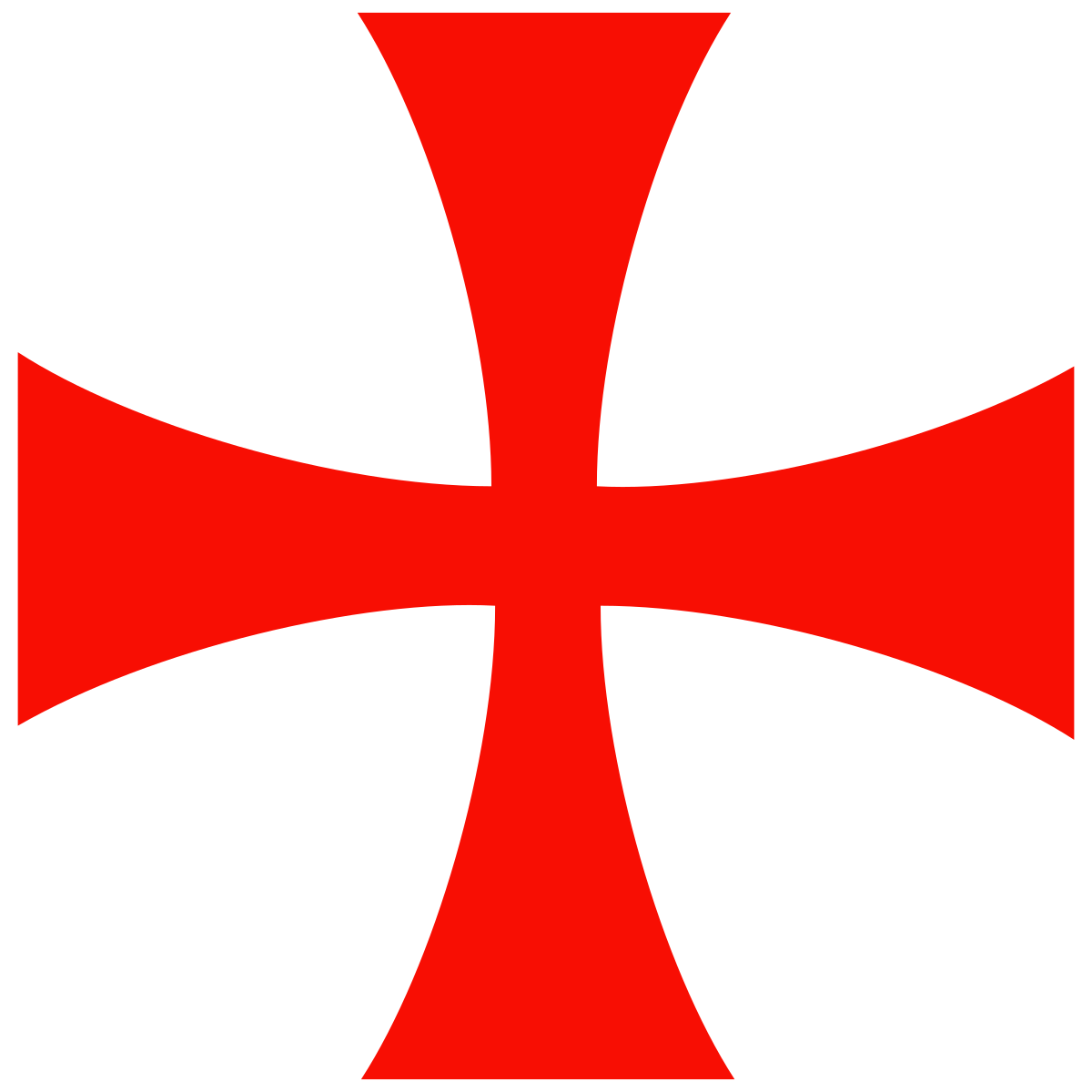

The Knights Templar Cross

A symbol of the Knights Templar, often a red cross on a white background. This Cross was used to symbolise martyrdom, and the knight’s belief that it was an honor to die protecting the Holy Land and its pilgrims.

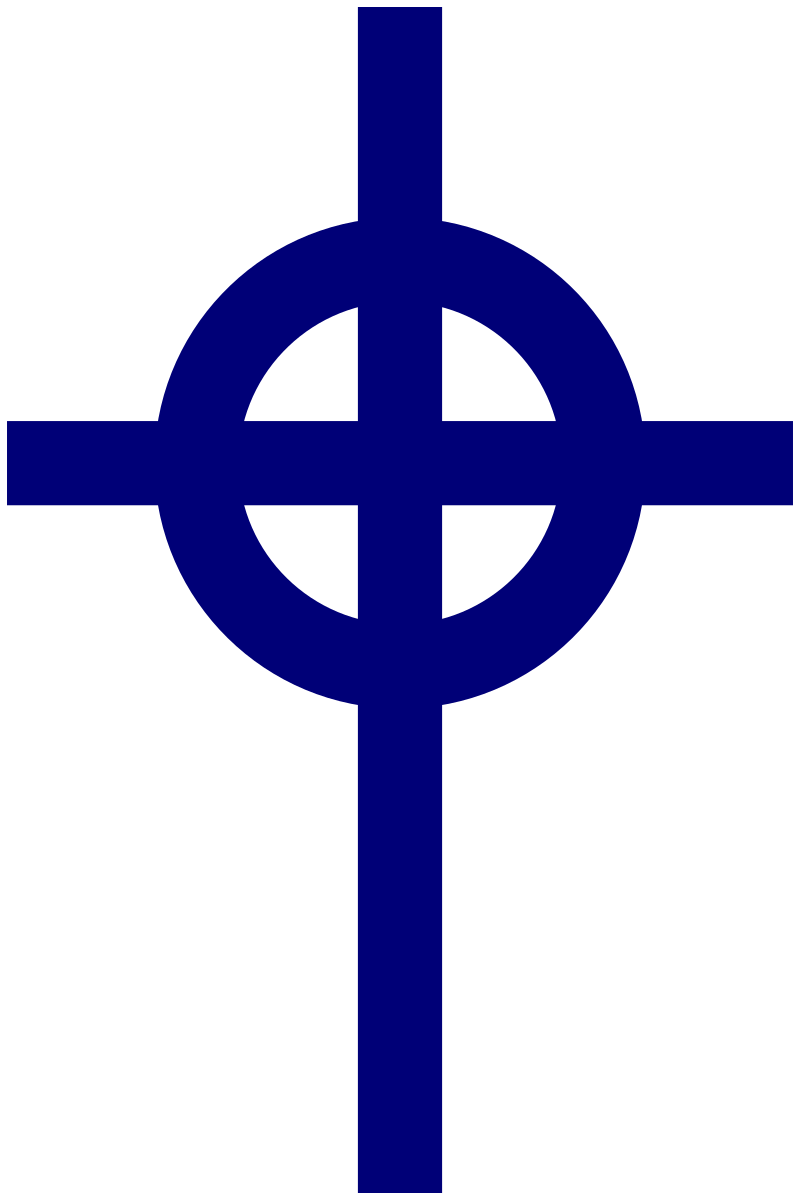

The Celtic Cross (in the Christian era)

A Latin or Greek cross with a circle, common in Ireland and Scotland.

There are two prevailing meanings for the symbolism of the Celtic Cross in Christianity.

The first is that when St. Patrick went to Ireland, he immediately recognized the importance of the large circular stones that the Druids worshipped as a symbol of eternity. The legend goes that St. Patrick would draw a Cross on top of these stones, and the Celtic Cross thereafter became symbolic of combining the two Faiths; the Cross representing Christianity, and the circle representing eternity.

The other is that the center ring of the Celtic Cross represents the Celtic symbol for infinite love (agape) - that with no beginning or end (Alpha to Omega). In this use it is symbolic of God’s endless love, and that the circle is also representative of the halo of Christ.

The Cross of Lorraine

A cross with two horizontal bars, this symbolic Cross was seen as the True Cross for Eastern Christian countries in the 12th-13th centuries, used on coins and as the sigil for Hungary. The upper cross is shorter than the lower one, representative of the titulus on which I.N.R.I (Jesus Nazareus Rex Iudeorum) had been written as a humiliation of Christ by the Romans at His crucifixion.

Bella III of Hungary was the first known monarch to use this Cross of a symbol of power in the 12th century, and it was then used by the Duchy of Lorraine for French rulers. This symbol would later be associated with Joan of Arc and then the French resistance.

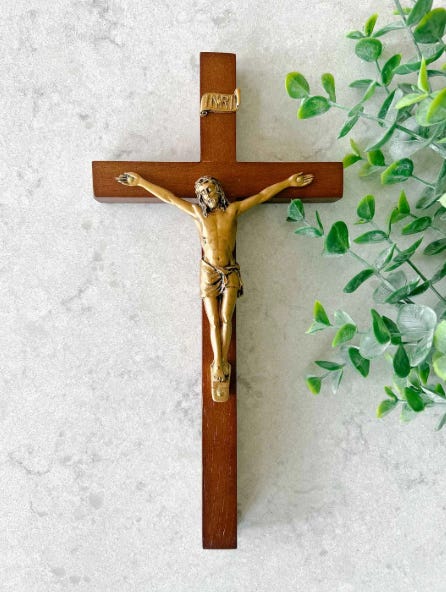

The Crucifix

A cross with the figure of Jesus, common in Catholicism, and the symbolism is pretty obvious.

The Marian Cross

A cross with an "M," representing the Virgin Mary (or Mother Mary, depending on your denomination). The placement of the M is meant to symbolize Mary’s presence at the foot of the Cross during the crucifixion.

This also signifies her role in salvation and highlights the deep bond between mother and son. It’s often interwoven with the Cross, signifying their unity.

The Budded Cross (Trefoil Cross)

A cross with clover-shaped ends, symbolizing the Holy Trinity.

The Canterbury Cross

This form of the Cross was selected in 1899 to surmount the Martyr’s Memorial in Kent, England, and has since become seen as representative of the Anglican Church. Used as a symbol of communion and cooperation, the “triquetra” pattern in the center of each arm is based on a Celtic knot design that symbolizes the Trinity.

The Canterbury Cross is also unique in its Byzantine and Celtic design influences. The intricate scroll work around each arm is a noteworthy example of Byzantium’s influence throughout Western Europe.

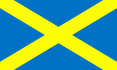

St. Andrew’s Cross

The Cross of Saint Andrew, also known as the Saltire, is a well-recognized symbol with a rich history and deep symbolism. This distinctive symbol consists of two diagonal lines crossing each other to form an “X” shape, reminiscent of the way Saint Andrew was said to have been crucified.

The Cross of Saint Andrew holds significant symbolism, particularly in Scotland, where it is the national emblem. It represents humility, martyrdom, and the willingness to sacrifice for one’s beliefs. Furthermore, the diagonal shape is also associated with dynamic movement and progress, making it a powerful symbol for unity and forward motion.

If you know your Biblical history, St. Andrew was also known as the “first called” among the Apostles. He was present at the Last Supper, and was among those who witnessed Christ’s ascension. After Pentecost, he is believed to have spread the teachings of Christ Jesus in Greece, Asia Minor, and possibly as far as modern-day Russia.

St. Peter’s Cross (the inverted Latin Cross, aka Petrine Cross)

As a result of the manner in which he was crucified, the Church has used the upside down cross (without a corpus, so not a crucifix) to designate Peter, not Christ. The Pope, being the successor of Peter, employs the symbol of the upside down cross as a symbolic reminder of St. Peter's humility and heroic martyrdom.

Traditionally associated with Peter’s crucifixion, this was later misused in anti-Christian contexts.

*Note: We have discussed the “inversion principle” used by nefarious actors as an affront to God in the previous On Statecraft and Religion: Identifying the Darkness posts. The inversion of the Latin Cross can be used to these ends by those groups, but was traditionally used to symbolize St. Peter.

https://open.substack.com/pub/robertplewis/p/on-statecraft-and-religion-35-identifying

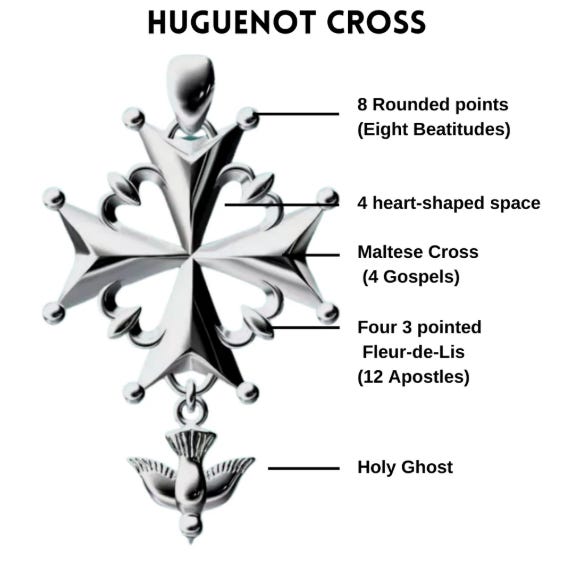

Huguenot Cross

A cross with fleur-de-lis, symbolizing the 8 Beatitudes, 4 heart-shaped space, 4 Gospels, 12 Apostles, and the Holy Ghost.

Coptic Cross

Ornate, often with equal arms and intricate designs, symbolizing eternal life. Each line terminates in three points, representing the Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Altogether, the cross has 12 points symbolizing the Apostles, whose mission was to spread the Gospel message throughout the world.

Teutonic Cross

Used by the Teutonic Order in medieval Europe. This emblem, known as the Teutonic Cross, became synonymous with the order's military and religious endeavors. It represented the Christian warrior ethos, combining the chivalric values of knighthood with the spiritual ideals of the Crusades.

The important differentiator between the Teutonic Cross and others is the capitals placed at the end, the presence of which denotes strength and power through Christ.

*Note: The Teutonic Knights were from medieval Germany, and post-WWII everything from Germany’s past became associated with Nazis.

Most of the renderings of Teutonic Crosses that you will find now are inaccurate, and those provided in image or Google searches will be versions of the Templar or other Crosses. The true Teutonic Cross has the capitals at the ends, as above, symbolic of the power through Christ.

Victoria Cross

Britain’s highest military honor, featuring a cross.

The Navy Cross

One of the US Military’s highest honors/awards.

St. Alban’s Cross

A yellow diagonal cross, symbolizing the first British Christian martyr. While St. Alban’s Cross does bear resemblance to St. Andrew’s Cross (Scotland), this one is said to be diagonal because he was beheaded, not crucified.

Fin

We’ve discussed the power of archetypes and archetypal symbols before, how they can become deep-seated in our ancestral memories, cultures, and personal understanding of the world. While the Cross is synonymous with the Christian Faith today, it is also one of the oldest symbols and archetypes in humanity.

After the crucifixion of Christ Jesus of Nazareth, the world changed in many ways. Once the Cross became synonymous with Christ and redemption through Him, many different representations, each with its own unique symbolism, began to emerge.

There are a few lessons that I hope people take away from this post:

Don’t immediately assume that a symbol represents evil or nefarious intent simply because you don’t recognize it.

There are many aspects of deep history, the Christian Faith, and its symbols that many of the most fastidious Church goers and Bible readers may not know. They are worth learning about, and many of these things have deepened my own personal Faith.

As the hubbub over Pete Hegseth’s Jerusalem Cross tattoo showed us, there is a serious issue with both of those takeaways in our current society.

The secular and nefarious will use the lack of understanding by the masses to try to drum up anger & fervor against those who may actually understand them, and who choose to utilize those symbols as their own testaments of their deep Faith (and knowledge).

The Latin Cross is enough for many Christians; some of us who know the historical roots of our Faith and its journeys over history choose more profound, and precise, representations of Christianity or the aspects of it that give us strength when we need it.

The big takeaway: when you see the secular media or “influencers” trying to form an outrage mob over some symbol, word, passage, action, or quote, take the time to actually look into it.

You would be amazed at how easy it is to actually research the origin of these things, and how stupid & lazy these secular journalists expect their audience to be that they wouldn’t take 30 seconds to look it up in advance of getting angry.

Do your due diligence, and don’t let the succubi lower your vibrational energy through manufactured outrage.

Stay happy, informed, and in the higher bounds of this amazing world in which we live.

Deo et Patrieae. For God and country.

I’m terrible at asking others for things, but…

It’s my intention to keep this platform free to read, but with the ability for people to donate if they are so inclined and feel the content here is worth their hard-earned dollars. These posts take quite a bit of time and research, but as I work it into my routine the flash-to-bang on new posts should reduce dramatically.

If you are so inclined and feel this is worth your time to subscribe for updates, share with others, or become a paid member, I’d greatly appreciate it.

Regardless, we’re all in this shitshow together. I’m going to do what I can to help you see the bigger picture and keep your eyes on the things that matter.

Until next time,

RPL